Sponsored by Medtronic Neurovascular

By Sean Hulsman for EMS1 BrandFocus

The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS), used for decades to identify potential stroke patients, has done well during its run as a field assessment tool. It is brief, simple to administer and accurately identifies patients who are suffering a stroke.

Its simplicity, however, has made it obsolete. With the advent of high-tech treatments for large vessel occlusions, there is a growing need for EMS providers to not only identify potential strokes but also to differentiate between types of strokes.

Neurology specialists are now engaged in research and debate about the best way to identify what type of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is occurring and to direct patients toward the most appropriate medical centers for their conditions.

What is Large Vessel Occlusion?

Large vessel occlusions (LVOs) are ischemic strokes that result from a blockage in one of the major arteries of the brain. These large vessels include the basilar artery, carotid terminus and middle cerebral artery, and occlusions therein cause loss of blood flow to significant portions of the brain. Higher-order brain functions tend to be disrupted, and these strokes tend to be more severe and result in less favorable outcomes for patients. (1)

While tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is the go-to treatment for about 25 percent of ischemic strokes(2), LVO presents an opportunity for neurovascular interventionalists to perform what is now considered the gold standard for stroke treatment: endovascular therapy (EVT).

Using advanced real-time imaging, guide wires and stent retrievers, neuro specialists enter the vasculature of the brain and physically remove the offending clots (thrombectomy), immediately restoring blood flow.

Only about 10 percent of AIS patients are eligible for EVT (2); however, those who are eligible need to be identified early and transported to a facility where they can receive this state-of-the-art care. The trouble is this: Although the CPSS is not capable of giving EMS enough information about the potential for LVO, many EMS clinicians still rely on it.

A recent EMS1.com poll found that while the CPSS is useless for any sort of AIS differentiation, just over 70 percent (814) of prehospital respondents use it as their primary stroke assessment tool.

Add to this the fact that 33.8 percent of EMS providers reported that they most frequently transport stroke patients to the nearest hospital (in lieu of a stroke center of any level), and it’s not hard to extrapolate that some patients who might benefit from advanced stroke care are not getting to the medical centers where they can receive such treatment.

Not all stroke centers are alike.

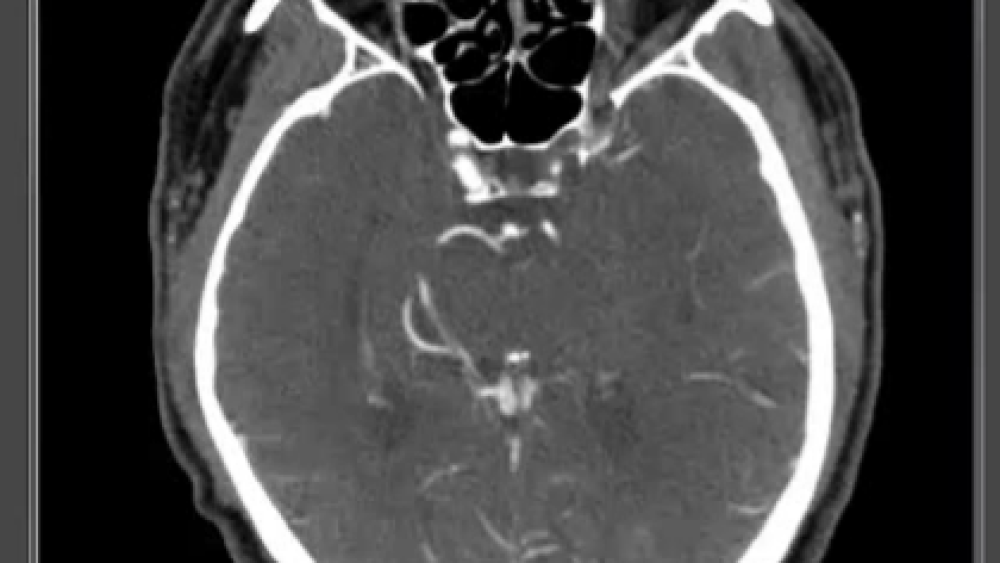

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) currently identifies three levels of stroke center. (4) The first, an Acute Stroke Ready Hospital (ASRH), is any facility that has 24/7 CT capabilities and can initiate tPA. CT is required to differentiate ischemic strokes from hemorrhagic strokes, to determine patient eligibility for tPA and is the only non-invasive procedure that can conclusively diagnose LVO. Training for ED staff at an ASRH is only required twice per year and core stroke team members must receive only four hours of training annually.

The second level is the Primary Stroke Center (PSC). The PSC must have 24/7 CT and MRI capabilities and must also be able to administer tPA. Some PSCs offer EVT, but it is not a requirement according to JCAHO. Additionally, core stroke team members at a PSC are required to have eight hours of annual training.

The third and most advanced center is the Comprehensive Stroke Center (CSC). A CSC must meet far more stringent standards for training, documentation, research and planning and must be able to offer several different treatment options for stroke, including endovascular therapy.

The differences between the training and capabilities of these three types of facilities underscore the importance of recognizing LVO early. Patients with LVO are candidates for endovascular therapy, and if EMS transports these patients to an ASRH or a primary stroke center without EVT capabilities, precious time is lost while the patient gets CT imaging and is then transferred to a higher-level care facility.

The term “Time is Brain” is commonly used in stroke treatment. For every 30-minute delay in reperfusion, the possibility of a favorable patient outcome decreases by 26 percent. (5)

What can be done?

Most physicians agree that the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is the best tool for triaging patients presenting with symptoms of acute ischemic stroke, but it’s a lengthy, cumbersome assessment that requires time many EMS providers don’t have during a patient encounter. Some headway has been made in developing new stroke scales, but none have yet emerged as the holy grail of prehospital assessment for LVO.

Nevertheless, there are some things that EMS can do in partnership with physicians and neurology specialists to give stroke patients a better chance for positive outcomes. To begin, providers can learn to identify specific symptoms and signs that might predict LVO. Some of the more common ones include conjugate gaze deviation, various forms of aphasia or language disturbance (dysarthria – simple slurring of the speech – is not considered a language disturbance (3) ) and agnosia (the inability to recognize objects).

These three symptoms are accounted for in the South Carolina EMS Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation (RACE) scale. A simplified version of the NIHSS called the NIHSS-8 has also been developed, and it, too, accounts for some of these LVO predictors. It should be noted that to date the efficacy of these and other assessment scales are not yet supported by significant evidence from any prehospital trials. (6)

Once an acceptable prehospital stroke scoring scale can be agreed upon, the next step is for regional medical directors and hospital systems to collaborate on guidelines outlining which facilities are most appropriate for a given patient.

As previously mentioned, not all stroke patients are eligible for EVT and therefore do not require transport to an EVT-capable facility. In the meantime, however, it seems that the best EMS option is to send all suspected stroke patients to a facility capable of endovascular therapy whenever possible. While we run the risk of swamping hospitals with patients that are not LVO or are otherwise non-candidates for EVT, this practice would provide operational assurance that the most critical stroke patients end up where they can be best treated.

About the author

Sean Hulsman, MEd, EMT-P is Director of Education at Twin City Ambulance Corporation in Western New York. He began his EMS career in 1992 and continues to teach and work in the field. You can contact Sean via his blog: Coarse Asystole.

References:

- Smith WS, Lev MH, English JD, Camargo EC, Chou M, Johnston, CS, Gonzalez G, Schaefer PW, Dillon WP, Koroshetz WJ, Furie, KL, Significance of large vessel intracranial occlusion causing acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009 Dec: 40(12):3834-3840. Doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561787

- Vanacker P, Lambrou D, Eskandari A, Mosimann PJ, Maghraoui A, Michel P, Eligibility and predictors for acute revascularization procedures in a stroke center. Stroke. 2016;47:1844-1849. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012577.

- Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine (2006, August 17). Clinical differentiation: Cortical vs. subcortical strokes. Retrieved from: http://casemed.case.edu/clerkships/neurology/NeurLrngObjectives/NeurLrngObj_Stroke01new.htm

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (2017, January). Stroke certification programs – Program concept comparison. Retrieved from: https://www.jointcommission.org/stroke_certification_programs_program_concept_comparison/

- Ribo M, Molina CA, Cobo E, Cerda N, Tomasello A, Quesada H, Angeles De Miquel M, Millan M, Castano C, Urra X, Sanroman L, Davalos A, Jovin T, Association between time to reperfusion and outcome is primarily driven by the time from imaging to reperfusion. Stroke. 2016;47:999-1004. Doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011721

- Demeestere J, Simplified 8-item NIHSS to identify acute ischemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion: a pilot study. Retrieved from: https://professional.heart.org/idc/groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/@scon/documents/downloadable/ucm_481666.pdf