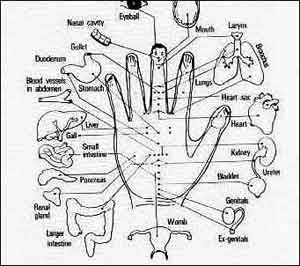

Acupressure points |

The number one reason why people call EMS is because of pain. The pain may be a heart attack, a fractured tibia, an aortic aneurysm, or something similar. Most patients don’t know the cause — all they know is that they hurt and want help. However, in the United States, we do a horrible job of prehospital pain management. We never really address the primary reason they call us: pain.

A more specific conundrum is the question of what basic EMTs and first responders can actually do to help patients in pain. The primary approach has simply been an application of the basics: placing the patient in a position of comfort, maintaining body temperature, and splinting fractures. But, can more be done by basic personnel?

First, I should note that I am of the opinion that EMTs should be able to administer nitrous oxide/oxygen mixtures (Nitronox). Unfortunately, the Food and Drug Administration, in their infinite wisdom (note: biting sarcasm here), will not allow nitrous oxide and oxygen to be premixed, even though it occurs in every other freakin’ country in the world.

Thus, instead of a single cylinder like those the Canadians and British have (Entonox), we have to have two separate cylinders that feed the gases into a gas blender in order to provide the patient with analgesia. As a result, U.S. prehospital nitrous oxide delivery device is bulky, expensive and rarely used. So, what else can be done?

There is a developing body of evidence that shows that Eastern medicine techniques (e.g., acupressure) can be effective in reducing pain, nausea and motion sickness. The quality and soundness of these studies is high, in that most are prospective, randomized controlled trials.

In 2002, Viennese researchers investigated the effectiveness of acupressure provided by prehospital personnel for victims of minor trauma. Acupressure is based upon the ancient practice of acupuncture, which was developed in China during the Xia dynasty (2140-1700 BC). It is based upon the theory that the flow of life energy (called chi) can be improved through the placement of needles or application of pressure at specific points on the body. While we have not been able to document the existence of chi in Western medicine, numerous studies have shown acupressure and acupuncture to be effective therapies for certain conditions.

In a minor trauma study, prehospital patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups. Group 1 received acupressure at known points: Di4 (Hegu), KS9 (Zhongchong), KS6 (Neiguan), BL60 (Kunlun) and LG20 (Baihui). Group 2 received acupressure at sham points. Group 3 was the control group and received no acupressure. The groups were comparable in terms of age, sex and type of injury. Their personal belief in acupressure did not differ significantly between the groups (equalized Pygmalion effect).

Following treatment, Group 1 experienced a significant pain reduction for all patients. Group 2 and Group 3 remained unchanged. Anxiety was reduced by 68 percent in Group 1 compared to 50 percent in Group 2 and 52 percent in Group 3. There was a significant decrease in heart rate in Group 1 patients while the heart rate in Groups 1 and 2 remained unchanged. After treatment, patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher for Group 1. Overall, this study is fairly compelling.1

In 2004, another high-quality study looking at the effectiveness of acupressure for motion sickness in geriatric patients was conducted in Vienna. In this case, the K-K9 point located in the middle phalanx of the fourth finger (ring finger) of both hands was used. This technique is based upon Korean acupressure practices rather than Chinese practices. In this study, 100 patients, who ranged in age from 60-100 years and who had a history of motion sickness, were enrolled. Patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: Group 1 received bilateral acupressure at the K-K9 point and Group 2 received bilateral acupressure at a sham point (on the index finger). Both groups exhibited an increase in nausea and perspiration before treatment. However, upon hospital arrival, patients in Group 1 had a lower heart rate and a significantly higher patient satisfaction rate.2

In 2006, the same group of Viennese researchers looked at the efficacy of auricular (ear) acupressure in elderly patients with hip fractures. Again, patients were randomized into a true bilateral auricular acupressure group and a sham bilateral acupressure group. Those in the true acupressure group had less pain, less anxiety, and a lower heart rate compared to those who received sham acupressure.3

There are still so many things in medicine that we do not yet understand. Acupressure, acupuncture and hypnosis seem effective for selected patients. Acupressure, because it is noninvasive and safe, may provide basic-level EMS providers with a technique to help make patients more comfortable.

As a physician, I am fairly traditional. But, I have an open mind. I think that massage therapy and similar physical therapies have a benefit. While I have never tried acupressure, I would like to learn it because I believe it has potential in the prehospital field. I also think it is important, and intriguing, to study this practice in the U.S. EMS system. Surely, there must be an EMT or two out there trained in acupuncture.

References

- 1Kober A, Scheck T, Greher M at al. Prehospital Analgesia with Acupressure in Victims of Minor Trauma: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blinded Trial. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2002;95:723-727.

- 2Bertalanffy P, Hoerauf K, Fleischhackl R, et al. Korean Hand Pressure for Motion Sickness in Prehospital Trauma Care: A Prospective, Randomized. Double-Blinded Trial in a Geriatric Population. Anesthesiology and Analgesia. 2004;98:220-223.

- 3Barker B, Kober A, Hoerauf K, et al. Out-of-hospital auricular acupressure in elder patients with hip fracture: a randomized, double-blinder trial. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13:19023.