A systems approach to developing Crisis Standards of Care (CSC), defined as a “substantial change in unusual healthcare operations and the level of care it is possible to deliver,” is critical for EMS systems preparing for any public health emergency.

In a webinar on March 26, hosted by NHTSA’s Office of EMS, presenters James G. Hodge, Jr., JD; Aaron Burnett, MD; and John L. Hick, MD; highlighted work conducted in Minnesota and discussed why CSC planning is so critical in the prehospital setting. Minnesota’s preparation for a surge in demand for EMS services during the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for local EMS leaders who may have to implement crisis standards of care in their communities was examined in detail. Watch a video recording of the webinar at the end of this article.

Key questions asked about Crisis Standards of Care and COVID-19

The presenters answered the following questions from the audience:

Some doctors want to volunteer to ride on the ambulance for shifts, but this is not covered in the agency’s malpractice insurance.

It is probably better to direct the volunteer to an organization such as the Medical Reserve Corps, where coverage and protocols are already in existence. This would then afford doctors appropriate legal protection.

Does the Federal disaster declaration impact EMTALA rules?

Yes - it does impact, as most of the rules are waived during the emergency.

Can individuals still be sued while practicing CSC? Or will a judge just throw the case out?

Gross negligence is not protected at any point in time is not covered. Acting in good faith may be protected.

Are there CSC for community paramedic programs in Minnesota?

There are no CSC, but in the after-action review, we will appreciate the role of the community paramedic. Care to the patient away from the hospital is a tremendous role for the CP.

Waiving regulatory requirements – how can we ensure we are not allowing totally untrained people from becoming involved?

A suspension of statutes does not suspend the responsibility of the EMS medical director who still must take responsibility for the decisions being made. It gives them the flexibility to make a responsible decision. It is therefore not an abdication of responsibility but a flexibility to adjust to the conditions. The key is to balance risk and benefit.

After 9/11, NIMS was developed. After this, should there be a system to develop a better pandemic response?

Do we need to be better prepared? Yes, we need to sort out the supply chain, PPE antivirals and more.

How can we legally defend on changing standards of care based on time of day versus changing once until the crisis is resolved?

We should offer resources in a normal way if the ability exists to do so. We owe it to our citizens to give the appropriate amount of response as available at the time.

Takeaways on COVID-19 Crisis Standards of Care

Here are the top takeaways from the NHTSA webinar on EMS Crisis Standards of Care.

1. Implementing Crisis Standards of Care in Response to Covid 19: Legal and Policy Issues

James G. Hodge, Jr., JD, LLM, director of the Center for Public Health Law and Policy at Arizona State University and a leading expert in public health emergency law, opened the webinar by discussing legal and policy issues. Hodge noted that in the COVID-19 pandemic, states of emergency have been declared all the way from local to global levels, from the WHO to local declarations of disaster. On the national stage, we saw the HHS Public Health Emergency declared on January 31st, the National Emergencies Act and the Stafford Act evoked on March 13th, and the Defense Production Act going live on March 20.

Contained within those declarations are many waivers that can change the practice and operation of EMS. EMTALA rules have now changed as hospitals have to prepare to cope with the surge, which as a result, may make our closest hospital a little further away. Rules affecting HIPAA’s Privacy Rule, identify who can be advised of COVID-19 positive patients and when providers can be notified that they had been in contact with a positive patient.

Waivers across some states, Minnesota included, have already relaxed EMS licensure requirements, altering the scope of practice and operational considerations for delivering a service. Additionally, issues that are not on the front line right now, but will influence the immediate future of treating a patient and reimbursement in terms of participation in Medicaid, Medicare and SCHIP, and telehealth are also amended.

The declarations and waivers allow EMS to, in simple terms, in all good faith, do the best for the most with the available resources at hand, using the crisis standards of care, which are defined as a substantial change in healthcare operations and level of care due to a pervasive or catastrophic disaster. It was pointed out that negligence, malpractice, tort, privacy infringement, discrimination or workers’ compensation may well provide potential legal challenges but, many legal protections apply in routine events and declared emergencies affecting healthcare workers and volunteers.

2. Minnesota EMS Crisis Standards of Care plan

Aaron Burnett, MD, FACEP, EMS medical director for the State of Minnesota and an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Minnesota, discussed Minnesota’s crisis plan. As a member of Minnesota’s State EMS Regulatory Board, Dr. Burnett has helped put in place recent changes to regulations to help communities and EMS organizations respond to COVID-19 across the state.

Dr. Burnett described Minnesota’s health geography of six level 1 trauma centers serving a state population of 5.6M citizens. The state has regionalized systems for stroke, STEMI, trauma, pediatrics and psych. EMS itself is governed by an EMS Regulatory Board, appointed by the governor with representation covering ambulance, volunteer and fire-based EMS, public health, public safety and more.

Additionally, the state has a Medical Direction Standing Advisory Committee which provides a forum for physicians to discuss prehospital care and work towards the improvement statewide.

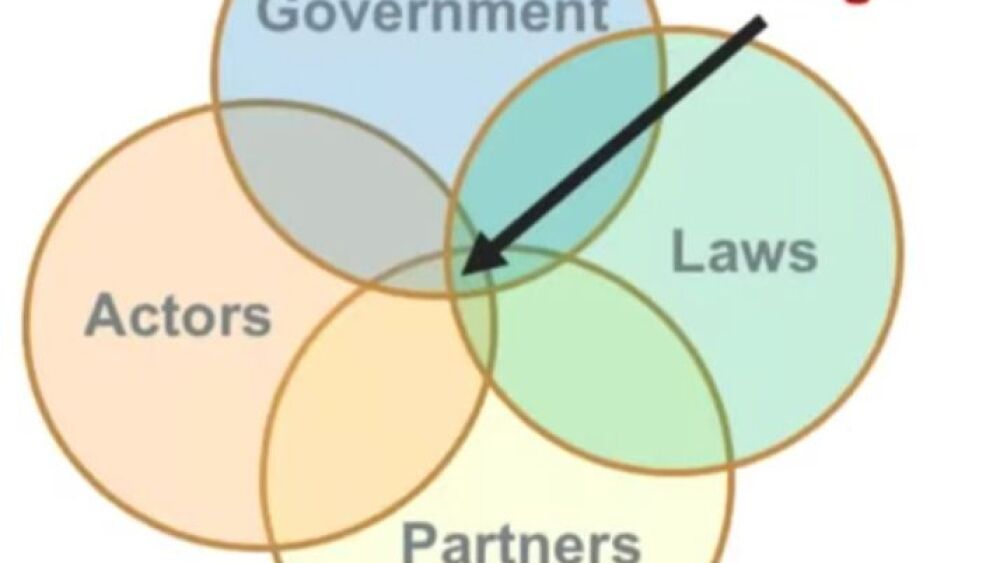

Dr. Burnett reported that the development of Crisis Standards of Care first began in 2010 after the H1N1 outbreak and has evolved over time in a very transparent way and in partnership with all elements of healthcare. Overall, the CSC represents the unified front for patient care in the state. Because of the development and relationships, when COVID-19 was declared, the system was mature enough to suspend regulations to allow the continued operation of EMS in the state without an overburden of regulatory constraints. Dr. Burnett was quick to point out that while regulations are suspended, all are expected to make their best efforts and complaint review panels remain in place to voice concerns.

3. The local EMS perspective: Operationalizing Crisis Standards of Care

The final speaker, John L. Hick, MD, identified the practical ways that the Crisis Standards of Care are being enacted. Dr. Hick is deputy chief EMS medical director and medical director for emergency preparedness at Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis. He is an expert on disaster response and advises the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response as the lead editor for the Technical Resources, Assistance Center and Information Exchange.

Dr. Hick identified that the operations of EMS and the levels and types of responses are determined by call volumes. By way of example (and this is playing out across the country), under normal operations, staffing continues as normal and within the agreed shift patterns and rosters, once the system moves to the contingency planning mode, then special events are curtailed, and supervisors and MDs are deployed to the streets.

As the event moves to crisis mode and calls reach a potentially overwhelming number, citizens then, (e.g., non-clinical drivers or National Guard personnel) could be used. For each phase of the response and call cycle, there is a well-defined set of actions. Additionally, as the crisis escalates, then the number of responders added to the call would be altered to reduce to a safe minimum, which mainly entails the reduction in the use of fire first response when an ambulance crew will be attending.

Do the greatest good

When the panel was asked to identify their final thoughts, the responses were simple but impactful: The big event, and it is here, you may or may not have planned for this, but start now, look at what is happening elsewhere and prepare.

If you can identify regulations in your state that you need to change to assist you, it’s a good time to reach out to legislators and seek change using local physicians to assist with the legislative effort.

Do the greatest good for the greatest number you can.

Additional crisis management resources

Learn more about Crisis Standards of Care and COVID-19 with these resources:

- Lexipol Coronavirus (COVID-19) Learning & Policy Center

- NHTSA Office of EMS: Coronavirus/COVID-19 Resources

- Network for Public Health Law COVID-19 Resources

- Minnesota Crisis Standards of Care

- COVID-19 breaking news and action items for EMS

- CDC updates EMS, 911 guidance for COVID-19