In some EMS organizations, the principles and practices associated with the science of improvement have been integrated into their DNA. These organizations monitor their performance in all vital areas of their operation, so that they are able to spot problems before they get out of control.

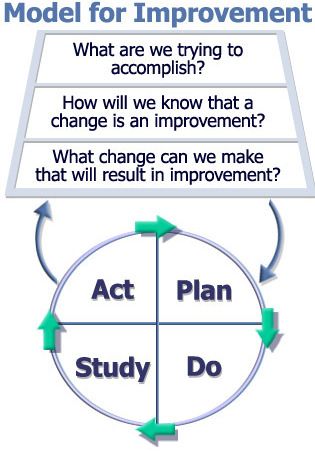

When something is not going well or a new opportunity shows up, they instantly charter a project using the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Model for Improvement. They are masterful at conducting small fast tests of change using Plan-Do-Study-Act to learn what produces the desired results in their system and what does not, before they implement. And they make measurable improvements to the things that matter to the people they care for, the communities they serve, the people that work on their team and their organization.

I am frequently asked, “How come most EMS organizations still don’t get it?”

We introduced these concepts more than 20 years ago. My default, when challenging questions like this, is to get curious. Curious about why this way of thinking is not more widespread. And on a more positive note, curious about how the leaders that have an improvement orientation hardwired into their mind and their organization got that way.

Look at success

One place to begin is by looking at a successful large-scale EMS improvement. In the late 2000s, Anne Clouatre MHS, EMT-P and the team from Centura Health in Littleton, Colo., introduced the concept of sepsis recognition and treatment to the EMS industry. Back then, very few EMS systems or providers thought much about sepsis. Anne and her team said that unrecognized sepsis kills lots of people and that EMS might save more lives with early sepsis recognition and treatment than we do with CPR and defibrillators.

Now as I travel around the country, 90 percent of the EMS folks I talk with have some type of sepsis protocol. One delighted BLS crew that I rode with last summer was proud that they had discovered more septic patients than their paramedic counterparts.

“What’s your secret?” I asked them.

“Every patient from a skilled nursing facility, every patient with a Foley catheter and every patient with recent change in behavior is septic until proven otherwise,” they explained.

If you wonder how this EMT crew that spends most of their day providing interfacilty transfer service developed this sepsis sense, neuroscience might have some clues. It also might help EMS leaders develop the improvement habit.

Neuroscience of EMS

My main teacher in the neuroscience of learning is our son Ax. When he was first learning to walk, I would play a little game with him. He’d be waddling along on unsteady legs and I’d quietly call his name, “Ax.”

He’d look over, fall down and chortle.

At five years old he can walk, run, scoot and skip without falling down when I call his name. Neuroscientists describe two modes of thinking that help explain Ax’s transition from having to give his full attention to the next step he takes to skipping along eating an apple while humming the theme from “Frozen” without falling.

Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel prize winning author of “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” calls these System 1 and System 2. System 1, also called the first brain or reptilian brain, operates automatically, so fast that you’re not even aware of it. System 2 is focused on mental activities that require your attention, your concentration.

Think back to the first time you got behind the wheel of a car when you were learning to drive. If you’re like most people, the radio had to be off, your first attempts at braking were bumpy and acceleration was either tentative or “slow down!”

Chances are, today you can drive in rush hour traffic while eating noodles with chopsticks and adjusting the radio volume.

Throughout our lives certain skills and knowledge move from the focused concentration required by System 2 to the tacit automatic System 1. That’s how Ax became a great walker, you became a great driver, some EMS providers have become great sepsis finders and any of us can become a great improver.

Making improvement automatic

There are a dozen of different processes and learning theories that help skills and knowledge move from System 2 thinking to the automatic System 1. Unfortunately, issuing a memo that says, “We will now be a performance improvement oriented organization” is unlikely to produce the desired results.

I’ve seen some leaders put the Model for Improvement everywhere; on their computer, on the visor of their car, as the screensaver on their phone. The concept is to expose themselves to it so much that they memorize it.

The Model for Improvement, which incorporates the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle. Used with permission from The Associates for Performance Improvement in Austin, Texas.

Others hardwire the questions from the Model for Improvement into the agenda for every meeting with elected officials, other agencies and employees. Starting a meeting by asking, “What are we hoping to accomplish today and how will we know if we have been successful?” is a powerful strategy to make this a normal, regular, System 1 part of your organization.

Whatever method you choose, including passing these columns along to the folks on your team, our hope is that you’ll learn to walk the principles of improvement so that you can skip along without hitting the dirt.