By Mike Taigman, Emily Tarr, Cole Miller, David Simek, Joel Enriquez, Justin Maldonado, Sam Williams

Are we really focused on what matters?

If someone crashed their bicycle on the street in front of wherever you’re reading this and shattered their right tibia, the chances are good that their pain scale would be north of five and EMS would respond. The arriving paramedic might:

- Do a quick assessment, start an IV, administer something for the pain (likely an opioid), wait for that special look in the patient’s eyes that lets you know the medication has kicked in, then splint the leg and load the patient for transport.

- Do a quick assessment, start an IV, administer something for the pain (likely an opioid), tell the patient that this is going to hurt a bit, then splint the leg and load the patient for transport.

- Do a quick assessment, tell the patient that this is going to hurt a bit, splint the leg and load the patient for transport, head for the hospital, start an IV and administer something for the pain.

- Do a quick assessment, say to the patient, “You don’t need anything for the pain do you?” Give the patient a high five when he agrees to go without pain meds, tell the patient that this is going to hurt a bit, splint the leg and load the patient for transport.

Are all four of these options possible in your system? I’ve posed this scenario to thousands of EMS leaders at conferences across the U.S. and 98 percent say that all are likely to happen in their system. If systems were as patient-centered as they claim to be, the care patients receive would be based on their clinical condition and local protocols – not on which paramedic shows up.

EMS quality improvement process

The quality management principle highlighted here is reliability. One of the functions of an effective quality improvement process is that it increases reliability so that all patients get the benefit of the best care no matter who shows up.

In the spirit of reliability, one of our goals with this column is to increase and align the effectiveness of EMS quality management practices across the U.S.

FirstWatch partnered with California State University San Marcos Assistant Professor Emily Tarr, PhD, and a group of her students to survey EMS systems across the U.S. and Canada about their quality management practices. The survey email was opened by 2,136 EMS leaders and providers – 492 of them completed the survey, for a 23 percent response rate. Those surveyed came from 41 states and four Canadian provinces.

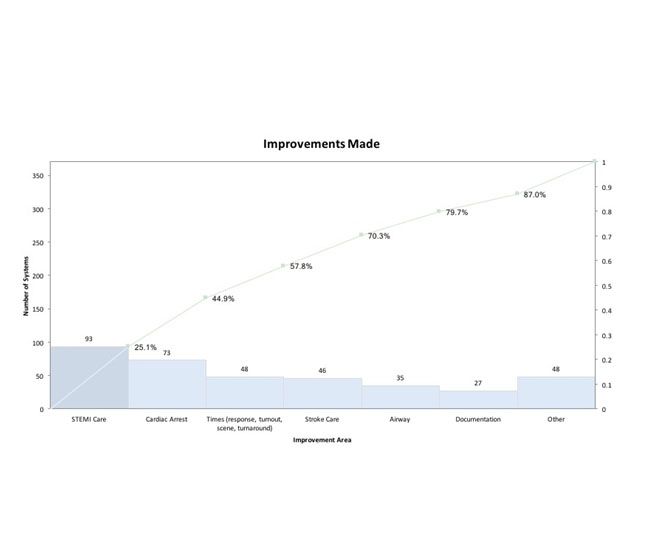

We asked responders an open-ended question, “What areas have you measurably improved and what data do you have to support this improvement?” Here’s a summary of what’s been improved:

- STEMI care: 93

- Cardiac arrest: 73

- Time (response, turnout, scene, turnaround): 48

- Stroke care: 46

- Airway: 35

- Documentation: 27

- Other: 48

It’s exciting to see so many systems making improvements in clinical areas that make a real difference for patients, though some of the answers confused monitoring performance with improving performance.

Having colorful charts, graphs, posters and reports about time to 12-lead for STEMI is interesting and might help with improvement, but it’s not improvement. “We reduced the average time from first ring of the 911 phone in the dispatch center to balloon inflation time for patients with STEMI from 106 minutes to 79 minutes” is actual improvement.

Identifying areas for improvement in EMS

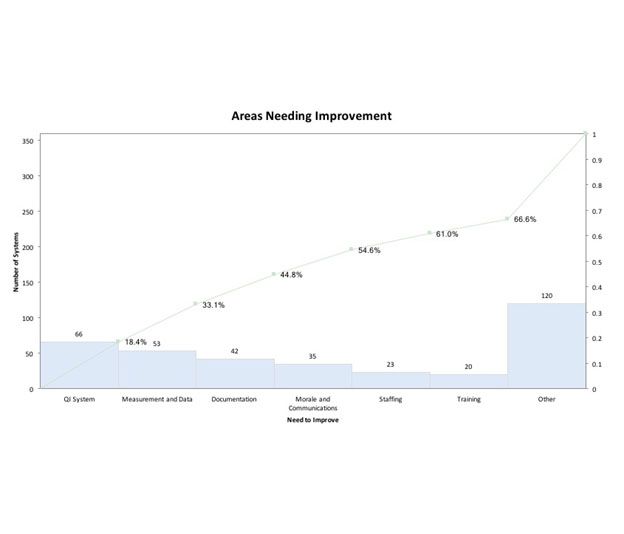

The answers that we received to the question, “What do you believe needs the most improvement in your system/organization?” were a little confusing. While a few systems focused on clinical areas like sepsis, pediatrics and airway management, most focused on leadership, operational and QI system issues:

- QI systems: 66

- Measurement and data: 53

- Documentation: 42

- Morale and communications: 35

- Staffing: 23

- Training: 20

- Other: 120

We asked the leaders who answered the survey if they share quality improvement-related information with their frontline providers. While 87 percent said they did, only 47 percent of the frontline providers said they receive feedback on their or their system’s performance from their leadership team.

It’s been well demonstrated that the closer in time feedback is provided on performance, the bigger impact it has on sustaining strong performance and improving substandard performance. Only seven of the respondents have systems that provide immediate or same-shift feedback.

Our hope is to move EMS organizations to implement quality management systems that focus on making actual improvements – improvements on things that really matter to patients, like surviving their cardiac arrest, sepsis or their opiate overdose.

Improvements that matter include shortening the time to re-establishing perfusion for people with STEMI and stroke. Decreasing their pain, nausea and difficulty breathing count as real improvements too.

Yes, improving staffing, QI systems, documentation and internal communication should help toward those goals that truly matter, but they don’t really count as goals in themselves – not if it’s your leg that’s snapped in two after crashing your bicycle.

About the authors

Emily Tarr, PhD, is assistant professor of management in the College of Business Administration at California State University San Marcos. Cole Miller, David Simek, Joel Enriquez, Justin Maldonado and Sam Williams are students at California State University San Marcos.