For those of us who are both EMS providers and parents, we can recall the plethora of potential disasters that entered our minds the first time our child developed a fever. Is it bacterial or viral meningitis? Do they have a hyperthermic disorder or a blood disorder like Sickle Cell Anemia? Is it a URI, UTI, or what?

More often than not, it just took the reassurance of our favorite ED doctor to calm us down, letting us know that it’s probably just a simple infection and nothing to worry about.

While it’s only natural to be concerned about your child’s fever, latest figures show that you should be concerned for your pediatric patients as well. Fever is one of the most common medical maladies in children and the source of approximately 25 to 30 percent of all ED and office visits. The definition for fever designates anything greater than normal — ranging typically from 96.0 F (35.6 C) to 100.8 F (38.2 C) depending on the time of day. A temperature above 107 F is usually caused by a more serious thermoregulation issue.

So what is the definition of a fever requiring medical attention? Most pediatricians do not consider a fever significant until it is greater than 100.4 F (38.0 C) in children older than three to six months. Some are even hesitant to administer treatments unless the child has signs or symptoms of other complications. Dr. Lou Romig, a pediatric emergency medicine physician in Miami, Florida (Miami Childrens Hospital), states that there are two main reasons to treat simple fever uncomplicated by other medical concerns: for patient comfort and for parent comfort.

It must be noted that fever in newborn infants less than three months of age may be a sign of a more serious condition. Although it is not uncommon for these little ones to have a normal or low body temperatures even if an infection or more serious condition exists.

Infection is the cause of most fevers. In an effort to fight infection, the hypothalamus increases the body’s temperature as part of the immune system’s activation. In a folk medicine sense, the body is trying to burn the infection out.

Children present with different signs and symptoms depending on their age. Infants most commonly present with:

- Irritability

- Fussiness

- Lethargy

- Unusual quietness

- Warm or hot to the touch (the better determination is with a thermometer)

- Doesn’t feed as normal

- Inconsolable crying

- Rapid respirations

- Changes in sleeping pattern

Besides the above, children with verbal skills may also complain of:

- General body aches

- Headache

- Difficulty going to sleep

Being able to identify the primary signs and symptoms of fever increases the EMS provider’s ability to assess the child, determine the criticality of the situation, and design the best therapeutic pathway.

When does the feverish child having a normal infection response warrant an emergent situation? The following current recommendations come from a combination of information from NAEMT’s Emergency Pediatric Care course, eMedicine Web site (http://www.emedicinehealth.com/fever_in_children), and a lecture by Dr. Lou Romig.

- 1) Children under the age of three months exhibiting a fever need to have a medical evaluation. This may entail something as simple as a consultation with their primary care provider or an evaluation by the ED staff.

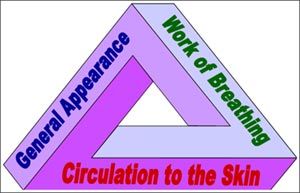

The Pediatric Assessment Triangle - 2) The Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) helps us look at the child’s overall status. If any of the triangle’s sides or any combination of them are less than normal, the child’s medical condition is suspect and a proper medical evaluation is required. If two or all three of the PAT aspects are questionable, this poor child should be considered emergent or urgent.

- 3) Any child with a fever unaffected by use of mild cooling processes and the proper use of antipyretics, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

- 4) Any child with an extended history of fever complicated by dehydration — not taking in fluids, vomiting, diarrhea, sunken eyes or fontenelle, dry diapers.

- 5) Any child that has seen their primary care physician or has been evaluated at the ED and continues to deteriorate must be re-evaluated immediately to ensure that a more serious complication is not present.

- 6) If the child has a seizure secondary to the fever or other medical complications.

Approximately 4 percent of all children will have a seizure secondary to fever, with a high occurrence in toddlers. Most commonly, the child’s fever will be greater than 102 F (38.8 C) and the seizure will occur on the first day of the fever. The older a child is when they have a febrile seizure, the less likely they are to have recurring episodes. Less than 2 percent of all the children who have had a febrile seizure have any further problems with a seizure disorder or epilepsy in the long-term.

Febrile seizures are typically more frightening for the parents than medically critical. Treatment for this form of seizure activity includes the following standards:

- 1) Protect the child from harming themselves during the event.

- 2) Do not forcibly restrain or try to prevent the clonic-tonic muscular activity.

- 3) Do not force anything into the child’s mouth in an attempt to protect the airway.

- 4) Provide a protective environment during and after the seizure by means of reducing the external stimuli such as excessive heat or cold, bright lights, excessive noise, excessive bystanders and gawkers.

- 5) Provide supportive measures including oxygenation and suction (as needed).

- 6) Make a transport decision based your medical evaluation of the child. This might include transport via EMS per protocols or transport by private vehicle, i.e. by the parents. Local protocols and medical direction should be actively involved in the decision process — on or off-line.

Reducing the fever, preventing dehydration, and assessing for more critical medical conditions are the three primary goals of caring for the feverish child. Determine if the parents or care givers have given acetaminophen (Children’s Tylenol, Tempra), ibuprofen (Children’s Advil, Children’s Motrin) or any other medications. It is vital that if any medications or remedies have been given, the dosage(s), time given, and method of delivery be recorded.

A child’s entire life is placed in your care and you must be diligent in your assessments and evaluations to assure that you find any indications of a life-altering condition, and treat them within your scope of practice. Document the information and report your findings and therapies to the next level of care.

Fevers can be confusing and frightening, regardless whether or not you are a parent, yet they are a common childhood malady. Fortunately, they are usually self-limiting and are commonly treated with supportive care and informed transport decisions.