“Medic-1 calling-in with a sepsis alert patient, 63-year-old male with a recent UTI, temperature of 101.7, blood pressure of 88/62 and respirations of 24.”

Sounds like a sick patient, right?

Sepsis, or septic shock, is the body’s extreme reaction to an infection. So extreme, in fact, that its mortality rate is roughly the flip of a coin: 50 percent.

Efforts over the past decade, however, have shifted the spotlight to this deadly disease process and have greatly improved its prognosis, that is, if it’s recognized early and treated aggressively.

Confusion or disorientation, shortness of breath, elevated heart rate, fever, shivering, extreme pain or discomfort, clammy or sweaty skin all are seemingly generalized symptoms that could root back to a number of acute or chronic disease processes. Included in this lengthy list is sepsis.

So, the task for EMS, or even in the hospital setting, is finding out how to objectively recognize sepsis. What are its common findings, its criteria? What constitutes a sepsis alert?

One method of determining sepsis in patients is utilizing the Quick SOFA, or qSOFA, score. This tool considers whether the patient has an altered mental status, increased respiratory rate or signs of hypotension, then evaluates their likelihood of sepsis involvement.

Additional tools, such as the Surviving Sepsis screening tool, incorporate the patient’s history of infection, laboratory values and signs of organ dysfunction into the equation.

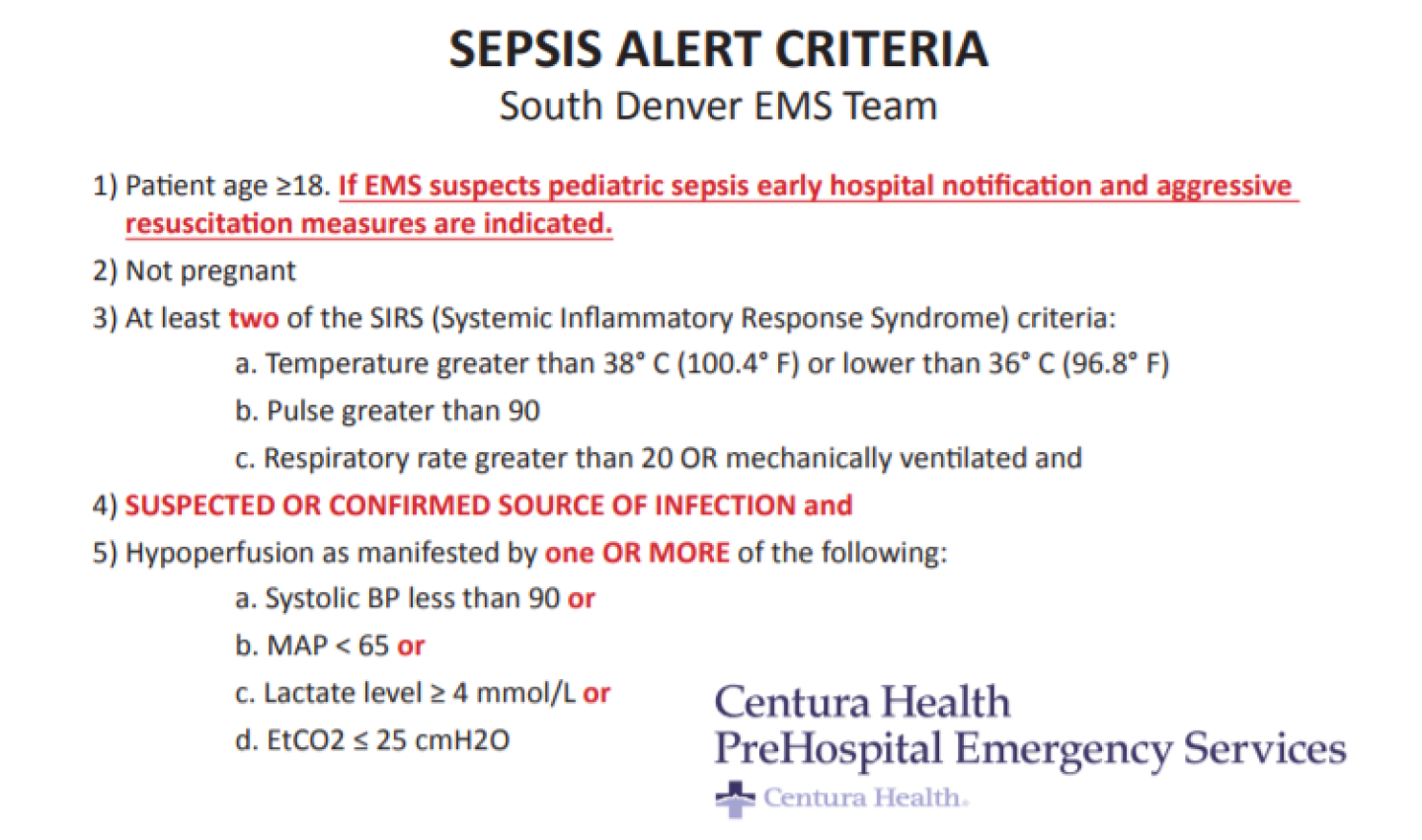

At the level of EMS, and even extending into the hospital setting, Centura Health’s Sepsis Alert Criteria simplifies the prior findings into a five-step evaluation, which also considers systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and end-tidal carbon dioxide as a prehospital assessment tool.

However, identifying sepsis in the field often prompts aggressive fluid management that can be utilized at both the BLS and ALS levels. Recommendations for 20-30 mL/kg of normal saline resuscitation are protocol dependent, but its effects are driving a 50 percent mortality down to near single-digits. Even with newer research results pending, it’s safe to say that EMS providers can recognize sepsis in the field, and EMS providers can legitimately save patient lives, decrease hospital stays, decrease the financial impact and aggressively treat patients in the field when it comes to sepsis.

What should EMS providers look for in patients?

While sepsis, or septic shock, can occur at any age, it seems that the majority of patients that we’ll likely encounter will be adults, or geriatric patients. It’s important to rule out any patients whose current medical status will result in atypical vital sign presentations, such as pregnant patients. Aside from these factors, three additional criteria can be evaluated to bring us to the differential diagnosis of sepsis.

- Infection. Without identifying a probable or possible source of infection, any alterations in vital signs or lab results could be due to a number of alternate causes. Common sources of infection for septic patients originate from the lungs, such as upper respiratory infections or pneumonia, and the urinary tract. Additional sources can come from the skin, such as inflammation, ulcers, and skin breakdown, the central nervous system, such as meningitis, or from the abdomen. While this isn’t an all-inclusive list, it does cover the most common sources that we’ll see in our transported patients, and certainly accounts for patients that will have a resulting elevated white blood cell count.

- SIRS. SIRS is an inflammatory state affecting the whole body. Because it is a systemic issue, its deficits can be seen in a variety of presentations. High-grade temperature (> 38 degrees C or 100.4 degrees F) or low-grade temperature (< 36 degrees C or 96.8 degrees F) fevers are a common finding of SIRS. In addition, systemic stress on the body can result in a pulse rate greater than 90, or a respiratory rate greater than 20, and can also indicate SIRS. In severe situations, some patients with an altered level of consciousness may even require mechanical ventilations, which also correlates to SIRS.

- Hypoperfusion. Septic shock, as a form of distributive shock, results in hypoperfusion from vasodilation. A systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg, or a mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 65, outline this finding. For agencies utilizing point-of-care lactate monitors, an elevated lactate level ≥ 4 mmol/L (or ≥ 2 mmol/L in some settings) indicates hypoperfusion. If assessing for lactic acidosis is not an option for you, recent correlations between decreased end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) and elevated lactate levels could bring you to a hypoperfusion finding. Most commonly, EtCO2 ≤ 25 mmHg indicates hypoperfusion, and can also correlate to an increased respiratory rate, meeting SIRS criteria.

Left undiagnosed and untreated, the results are certainly not in the patient’s favor. When recognized in the field and an alert is called, patient outcomes are clearly better. Fluid resuscitation is aggressively initiated, antibiotics are administered earlier in the hospital setting and the risk of mortality decreases, along with the patient’s length of stay in the hospital.

Good things come with progressive and aggressive patient management of sepsis, and EMS personnel are a huge part of this success. So, the next time you’re faced with a sick patient that has an infection, SIRS and is hypotensive, think about a sepsis alert.