This feature is part of the premiere edition of the EMS Trend Report, which takes an in-depth look at EMS trends in the United States and sets a foundation for assessing how the EMS profession is changing. Be sure to share this trend report with other EMS leaders and discuss your thoughts on how EMS is changing in the comments.

A key principle in physics says you can either know where an object is or how fast that object is moving, but you can never know both at exactly the same time. Trying to take the pulse of the nation’s EMS system can face the same challenge: While some things seem to stay stagnant, many aspects are changing so quickly that by the time they are measured and analyzed, they are no longer the same.

The EMS Trend report is not only about measuring where EMS is today, but also how fast — or slow — it is moving, and in what direction.

Survey scope

Instead of attempting to survey thousands of self-selected agencies, a group that can change from year to year, we focused on a smaller but still representative group of EMS agencies that agreed to take the time year after year to provide detailed information. We asked this group, which we’ll call the State of EMS Cohort, about their clinical care, operations, finances and more in order to examine trends within the industry.

The agencies selected to participate are not necessarily the “best” or the biggest. Instead, they represent a range of service delivery models and sizes in diverse geographic and demographic settings. They are diverse in many other ways as well, from clinical protocols to operational procedures.

Fitch & Associates, EMS1 and NEMSMA thank each organization that volunteered to participate in this effort. Without your willingness to share information for the betterment of patients and EMS systems everywhere, this project would not have been possible.

Highlights from Year One

Clinical Care

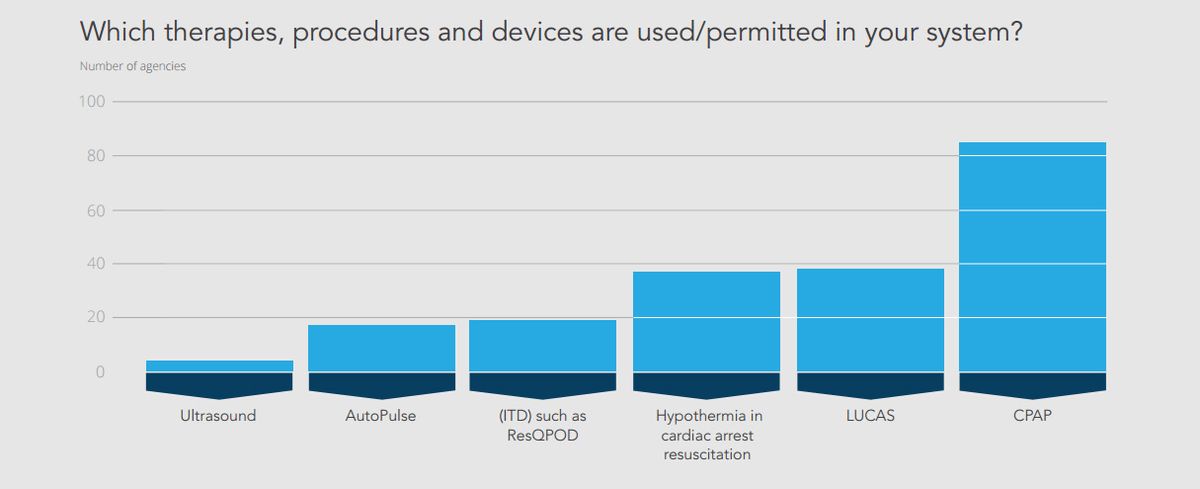

While an expanding research base and move toward evidence-based care has likely created more consistency in clinical protocols used across the country, some significant differences clearly still remain. Certain procedures and equipment are used by only a minority of agencies in the survey. Others have seen rapid adoption or decreased use in recent years.

For example, more than half of the agencies in the State of EMS Cohort now report using mechanical CPR devices, such as the LUCAS or AutoPulse. Yet at the same time, only a quarter report the routine use of impedance threshold devices for cardiac arrest patients. This being the first year of the trend report, it will be interesting to follow whether ITD use increases or decreases in future years, especially as the evidence of its effectiveness continues to be debated by experts in the field.

Perhaps not surprisingly, nearly every agency reported use of CPAP, a device that just 15 years ago was probably used only in a small number of systems. What procedure, medication or device will be the next to so dramatically change EMS care?

Currently, fewer than 5 percent of the State of EMS Cohort agencies use ultrasound in the field. It will be interesting to track that number over the next few years to see if more agencies decide ultrasound is a useful prehospital tool.

Another trend to follow will be the use of hypothermia in resuscitation. Fewer than half of the agencies reported that their protocols included therapeutic hypothermia for cardiac arrest.

The release of the most recent American Heart Association resuscitation guidelines, which recommended against prehospital administration of cold saline to induce hypothermia, occurred as this survey was being conducted. While the guidelines did not say to stop cooling in the prehospital environment, some agencies likely removed post-resuscitation hypothermia from their protocols completely, while others may have turned to an alternative method, such as ice packs.

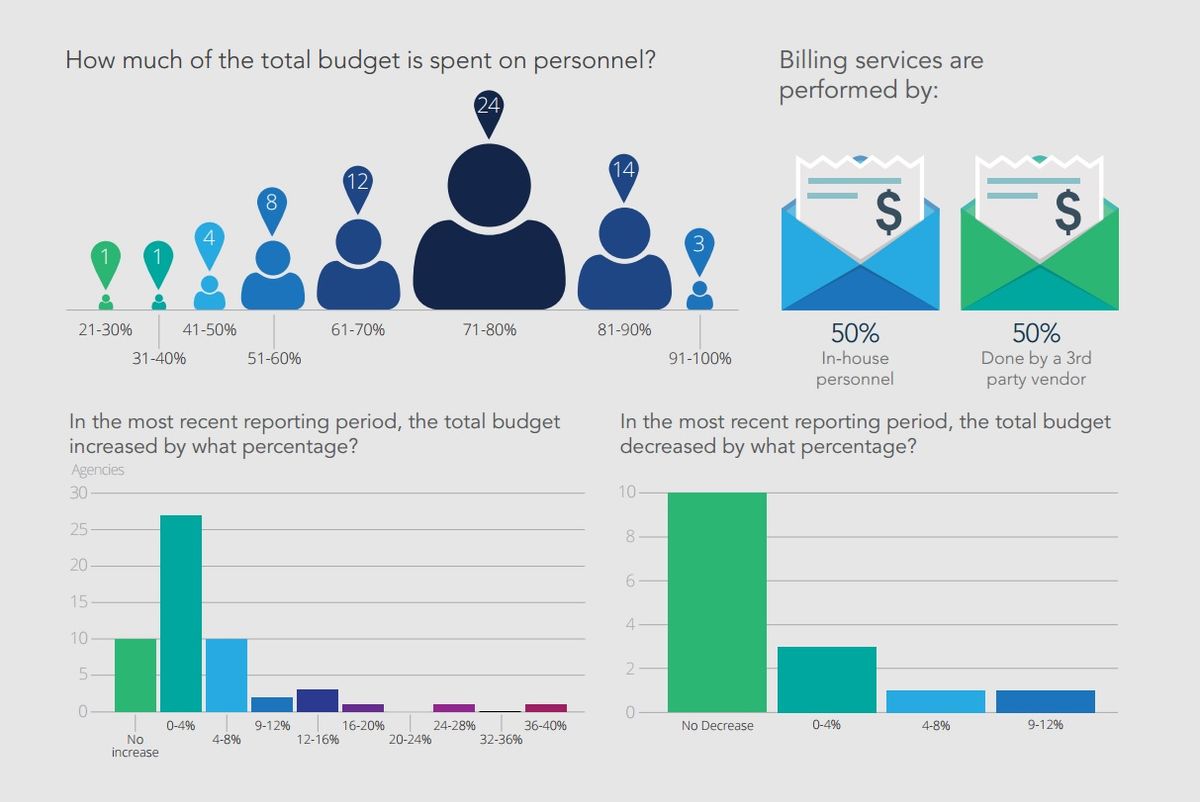

Finance

The economy’s slow but steady recovery seems to be reflected in EMS budgets. The majority of the agencies in our survey reported either no change or small increases in budget dollars over the previous year, while less than 10 percent reported a decrease. At the same time, almost none increased the budget by more than 4 percent, and with rising expenses and call volumes in many areas, these minimal increases are forcing many EMS organizations to try to do more with less.

Personnel costs represent the largest chunk of the budget for most agencies, meaning that stagnant budgets are likely leading to only modest, if any, increases in salaries or benefits.

Historically, emergency telecommunications jobs were considered positions for field providers who could no longer perform those duties or as entry-level positions. But recognition of the critical role of 911 call-takers and dispatchers, and the stressors and demands of the job, has led to a professionalization of the role, and increases in pay along with it. In fact, agencies report higher typical starting salaries for telecommunicators than EMTs in the field; however, paramedics continue to earn more.

Interestingly, the survey respondents were evenly split on billing, with half using a third-party vendor for ambulance billing and half using in-house staff. The impact of ICD-10, along with future changes to Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement policies, will likely drive how quickly and in which direction that answer shifts in future years.

Clinical measures

Certain indicators, such as return of spontaneous circulation in cardiac arrest and the ability to identify ST-elevation myocardial infarction, have been used to measure clinical performance for many years and remain in widespread use in EMS systems. In contrast, other measures have not yet been widely accepted, such as pain management, recognition of sepsis or heart failure and use of physical or chemical patient restraints. About half of respondents reported measuring a patient’s pain, for example, while the vast majority said they track their providers’ ability to identify STEMI.

The clinical indicators used demonstrate that some agencies still struggle to measure the right things, due either to lack of access to data or simply tradition. Nearly every agency is tracking ROSC, while slightly fewer track survival-to-hospital discharge, even though the latter is considered a more patient-centered and appropriate measure of the performance of the emergency care system.

Clearly, more EMS agencies need to have access to outcome information and other data from hospital systems and other sources in order to appropriately measure and improve the quality of care they provide.

Response time

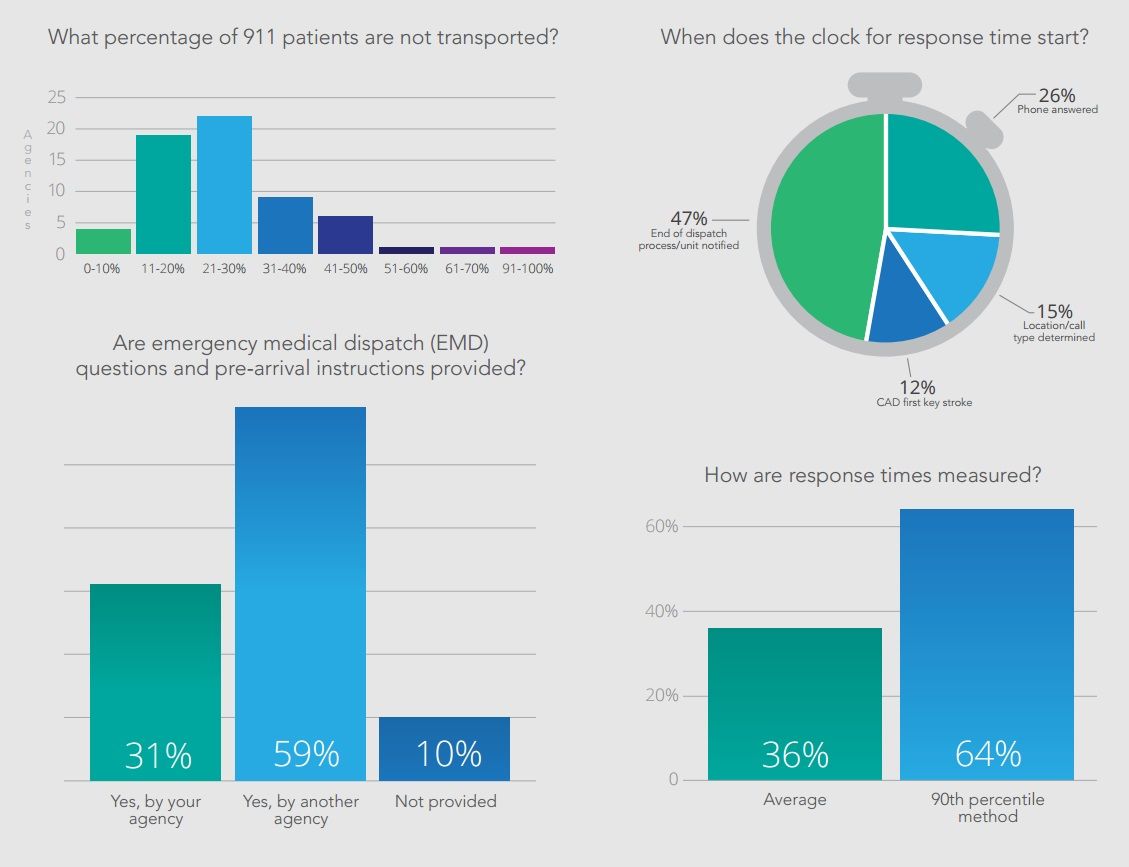

Response time analysis continues to be somewhat controversial in EMS. In recent years, an effort to focus on clinical and outcome measures has led many to argue that response time measures are outdated and irrelevant. However, response time is still an important measure for any EMS system, as it is critical in certain, rare situations (such as sudden cardiac arrest), and response time goals are often embedded in contracts and budgets.

Survey respondents differed widely on how they measure response time — a problem given that many compare themselves to each other and to benchmarks, such as the National Fire Protection Association standards. This survey found that 26 percent of respondents, for example, started the clock for response time when the phone was answered in a dispatch center, while 47 percent started measuring when the unit was notified. About two-thirds of the organizations surveyed said they measure 90th percentile times, while the rest measured average response times. This lack of consistency can lead to unrealistic expectations that often impact budget and resource allocation decisions.

Patient satisfaction

The widespread adoption of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Triple Aim” has led to increased use of patient satisfaction as a measure in health care, including for determining levels of reimbursement.

EMS has joined this movement but lags behind its health care partners. About half of respondents are not formally surveying patients, relying instead on unsolicited complaints or comments to assess patient satisfaction. About a quarter of agencies are using a third party to measure patient satisfaction. That number is expected to grow as more EMS agencies try to demonstrate community support.

Paramedic education

In recent years, the EMS community has debated whether more education should be required for paramedics. Some have argued that paramedics should, at minimum, hold an associate’s degree. Others have pushed further, saying that bachelor’s degrees should be necessary.

Among the State of EMS Cohort, fewer than 10 percent of agencies require paramedics to have an associate’s degree at this time, and none require a bachelor’s. However, it will be interesting to see if that changes in future years, as more than 60 percent of respondents think an associate’s degree should be required. Whether reality catches up with those opinions will likely be determined by many factors. Paramedics with degrees likely have higher salary expectations, especially if there is a scarcity of qualified applicants for paramedic positions requiring a degree.

Integrating EMS in health care

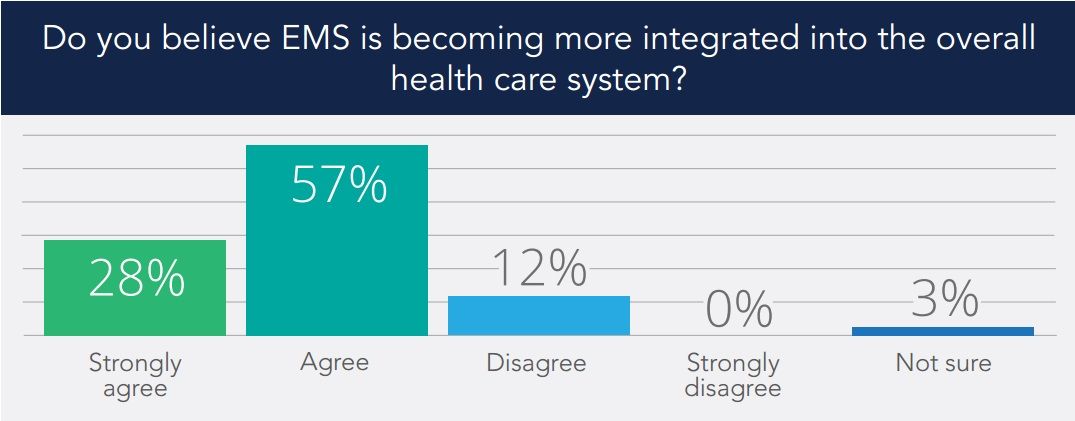

Only 11 percent of EMS leaders surveyed disagreed with the statement that EMS is becoming more integrated into the overall healthcare system. The vast majority agreed with the statement, with 28 percent answering “strongly agree.”

While there was general agreement on this question, there was less consensus on whether the term “emergency medical services” still best describes the profession. A handful said “EMS,” while many preferred “mobile integrated healthcare” or simply “mobile health.” Others suggested “prehospital care” or simply “paramedicine.”

Conclusion

The 2016 State of EMS report establishes a baseline for evaluating trends in the EMS profession as organizations in the State of EMS Cohort grow, innovate and mature over the years. With the EMS Agenda for the Future turning 20 in 2016, and an updated Agenda in the works, the State of EMS report will give our profession the opportunity to evaluate our current state and examine our progress toward achieving the goals we set for the next several decades.

Take a look at the survey results and consider what they might look like next year, in five years or in 20. When we look back at this first State of EMS report in 2036, what will it tell us about the next two decades of EMS?

A wide variety of EMS systems throughout the United States represent an assortment of system models, designs and structures. To reach the largest number of agencies for this survey, numerous outlets were used to solicit voluntary participation. These included the EMS1.com website, email contacts from Fitch & Associates and the National EMS Management Association, social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter and press releases from industry partners.

The survey was open for a 12-week period in 2015. Applicants were asked to complete a basic intake survey, after which staff at Fitch & Associates provided each applicant with an individualized survey link to complete the data entry process online. Applicants, especially those who did not fully complete the survey mechanism, were contacted with follow-up inquiries.

Staff at Fitch & Associates collected, aggregated and analyzed the data. Every effort was made to ensure that sufficient data points were reported by region and system configuration while still providing anonymity to the individual reporting agencies.

A total of 94 agencies — the “State of EMS Cohort” — participated in the survey. Not every department was able to provide answers for every question, so some questions reflect the responses of a subset of the agencies surveyed. More information about the survey respondents is available in the Survey Demographics section later in the report.