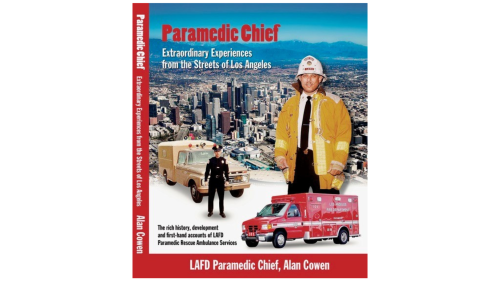

Editor’s Note: In “Paramedic chief - Extraordinary experiences from the streets of Los Angeles”, Chief Alan Cowen walks us through the early history of the City of Los Angeles Emergency Services, from horse-drawn firefighting equipment and ambulance carriages, up through today’s modern department that has become a model for the entire country.

Chief Cowen takes us into the common centers and on-scene to some of the city’s largest emergency events, including wildfires, earthquakes and civil unrest, and recounts how the LAFD transformed into the professional department it is today.

By Chief Alan Cowen

Even as a child, I could identify an approaching fire engine, police car or ambulance by the sound of its siren. By the time I was 10, I had memorized the pitch and depth of sound for each vehicle. For most people, that would be overkill, but it wasn’t enough for me.

I got to know all of the drivers and knew each one’s peculiarities. For example, Floyd “Pappy” Fair, driver of G-14 out of the Venice Police Station, always kept the ambulance siren at its highest pitch and frequency for a long time before he let it drop. At the time, I didn’t realize I wanted to be like Pappy. My skill at identifying sirens was just a game. That all changed when I was 10.

I was playing outside with my black mixed terrier, Candy, when I saw his ears perk up at the sound of a tremendous crash, and I imagined shattered glass and mangled debris on the railroad tracks. It took only a moment to lock Candy in the house and race toward the sound. I was afraid of what I was going to see, but an inner force propelled me on.

A light rain had made the sidewalk slippery, and I took extra care to not lose my footing. At the end of the first long block, I could hear the distant siren of a fire engine approaching. The low-pitched siren was a “growler” – my name for the Culver City fire engines. I wanted to beat it to the scene. As I passed Washington Blvd. my side ached but I couldn’t stop. The same morbid curiosity that causes people to stop at crash sites carried me along too.

The crash had happened on the railroad track at the corner of Culver Blvd. and Berryman Ave. - about two blocks south of my house. I had lived there my whole 10 years and liked watching the trains go by. Sometimes I put a penny on the track and let the train run over it so I knew how much destruction a train could create.

I arrived at the accident site just ahead of the fire truck. A police car was already on scene, and people stood around talking and pointing to the crash. No one knew what to do. It was my first time seeing the helplessness of hysterical bystanders. Years later, as a paramedic, I saw it often. I called it the “hands-on-head syndrome.” But that day, I was one of those bystanders.

An eastbound freight train with a gigantic wooden bumper had struck a car, leaving several passengers trapped and critically injured – some of them actually under the train. The vehicle was a piece of twisted wreckage and only shreds of wood remained of the train’s bumper, but the train seemed to be untouched.

I stood frozen to the spot and wished my dad was there. He was always so calm, and I thought he could make things OK. I suddenly realized that I didn’t know what to do either, and watching the adults lose control of the situation made me terribly afraid. Then, the heroes came. I watched in awe as the firefighters rode up, standing on the back bumper of the engine in their heavy turnout coats, big boots and traditional helmets. As they passed me with their emergency equipment, they looked so tall and strong. But more important, they brought order to the chaos. The assembled crowd moved aside to let the firefighters through to the shattered vehicle, where they used oversized crowbars to extricate the victims.

It was no surprise when the brown Los Angeles City Receiving Hospital Ambulance arrived. I had already recognized the approaching siren. Two men got out wearing police-like uniforms with shoulder patches that identified them as “Emergency Medical Los Angeles.” As a frantic woman screamed, “Hurry up; hurry up, quick!” the ambulance driver looked her in the eyes, snapped his fingers and said, “Take it easy lady. One thing at a time.” Even as a kid, I was impressed by his sense of calm. As I watched him and his partner place a rubber splint on a patient’s leg, I knew I wanted to be just like them. I stayed until the last tow truck was gone, deeply affected by what had happened.

For this 10-year-old kid, the last hour had been life-altering. I thought about the accident for days. How could I become one of those rescuers? How could I learn to do what they did so I could ride on a city ambulance? The seed had been planted – a few years later, it would start to grow.

- Excerpted with permission from “Paramedic chief - Extraordinary experiences from the streets of Los Angeles,” by Alan Cowen

- Self-published (2023)

- Available on Amazon

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Born in Santa Monica, California, Alan Cowen grew up in Culver City, California. He earned his B.A. in Speech from California State University, Northridge. Later he obtained a B.S. in Biology and a Master’s Degree in Education with a specialty in Counseling and Guidance. Concurrently, he was continuing his work in the field of EMS. In 1974, just 4 years after the Los Angeles City Fire Department took over the Los Angeles Receiving Hospital System, Cowen became one of the first field paramedics. He rapidly rose to lead paramedic and in 1980, was promoted to paramedic supervisor (captain). In 1985, he was promoted to assistant commander of the Bureau of EMS, and in 1987, he was promoted to chief paramedic and commander of the Bureau of EMS. In 1995, he was promoted to fire deputy chief. Cowen also obtained a Doctor of Chiropractic degree (DC) and continues to be licensed as a Mobile Intensive Care Paramedic (MICP), as he has for the last 50 years. He is currently a professor of fire technology at Los Angeles Valley College, where he is the EMT program director.