By Rob Wylie

What is a resilient community?

According to the Community & Regional Resilience Institute, resilience is “the ability to anticipate risk, limit impact and bounce back rapidly through survival, adaptability, evolution and growth in the face of turbulent change.”

As a 30-year veteran of fire and emergency services, the holy grail for me has always been to assist the communities I served to become resilient: to prepare for natural disasters, such as tornadoes, floods and fire; and to prepare individuals and groups (neighbors) to stand on their own for a period of time until the fire department can get to them, especially during a disaster.

To that end, we have spent countless hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars training people in things like CPR and basic first aid, but the basic underlying premise had always been: “We (the fire department) are coming, and when we get there, get out of our way.”

The issue with the “I will just call 911 and a police officer, firefighter or medic will magically appear and solve my problem” premise is that it really doesn’t work that way.

Response times

When attendees at a recent First Care Provider class I taught were asked, “what do you do in an emergency?”

The answer was unanimous: “Call 911!”

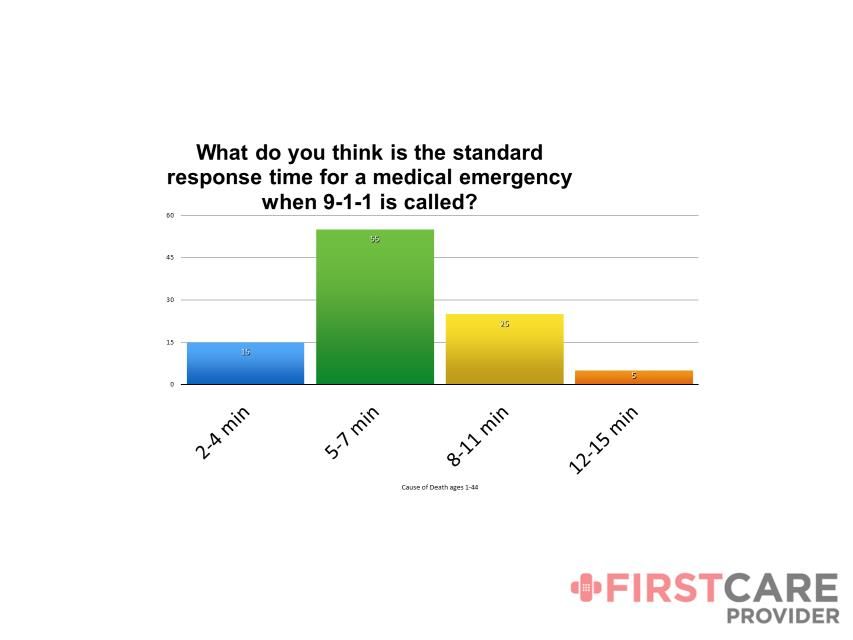

When the same group was asked, “how long do you think it will take a responder to get to you after you call 911?”

The most popular answer was 5-7 minutes (Figure 1).

The dirty little secret no one wants to address is that it takes as few as three minutes to bleed to death from a traumatic injury. It takes time for responders to be notified and to make their way to the scene of the emergency. When someone is dying, time is a matter of life and death.

While 5-7 minutes is certainly an acceptable response time for emergency responders in many communities, in other communities, like Barrow, Alaska, where my colleagues and I recently taught a First CARE Provider class, the response time could be hours or days depending on such variables as weather and distance. The North Slope Fire District is responsible for over 90,000 square miles.

While Barrow represents an extreme example of prolonged response times for emergency responders, in fact, even in a metro or suburban area, response times can vary greatly depending on the scope of a disaster, the number of concurrent emergency calls resulting from that disaster and the number of responders available at any given time.

The International City Managers Association set the acceptable rate of emergency responders at about 1 responder for every 1,000 residents. That translates to very few responders when a major incident occurs, like a tornado or a hurricane.

Survivability

We invest numerous resources in training people to perform CPR, use an AED and provide basic first aid. An American Heart Association report suggests 326,200 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests occur annually. The average survival rate is 10.6 percent and survival with good neurologic function is 8.3 percent.

Compare those statistics with those that list trauma as the number one cause of death in people between the 1-45 years of age, with an economic impact annually of $400 billion, of which 20 percent are considered to be survivable with proper intervention, and you are looking at 30,000 lives saved annually.

Survivable injuries include bleeding to death (exsanguination). Uncontrolled post-traumatic bleeding is the leading cause of potentially preventable death among trauma patients, according to the World Health Organization.

If proper interventions are performed within the first 3-5 minutes for injures such as critical bleeding, there is a 90-percent chance that the injured person will survive.

With that in mind, we get a much bigger bang for the buck or return on investment teaching civilians to use tourniquets than we do teaching CPR.

Before the hate mails starts, I fully support teaching CPR. It saves lives. But a broader, more comprehensive approach is needed.

Redefining first responders

To build truly resilient communities we first have to dispel the myth that emergency responders will solve all of our problems. We must acknowledge that for the first 5-7 minutes in an emergency, the true first responders are the people who are present at the time of the incident.

Teaching those First Care Providers to deal with traumatic injuries will save lives and empower those who receive the training to make a difference rather than just calling 911 and hoping help arrives in time. One thing I have learned over the past 30 years is that hope is not a plan.

I am not advocating that people sitting at home see or hear a story about a bus accident and leap from their chairs to go render aid. I am talking about teaching the people who may be on that bus sitting next to their child, spouse or friend to act and to save that loved one’s life by compressing a bleeding wound, applying a tourniquet or relieving an airway obstruction.

We as emergency responders have to get past the idea that we are the only ones who can help in these situations. Civilians with a modest amount of training can make a difference when it comes to traumatic injuries such as critical bleeding (tourniquets and wound packing), airway obstruction (Heimlich maneuver) and breathing problems resulting from trauma (chest seals).

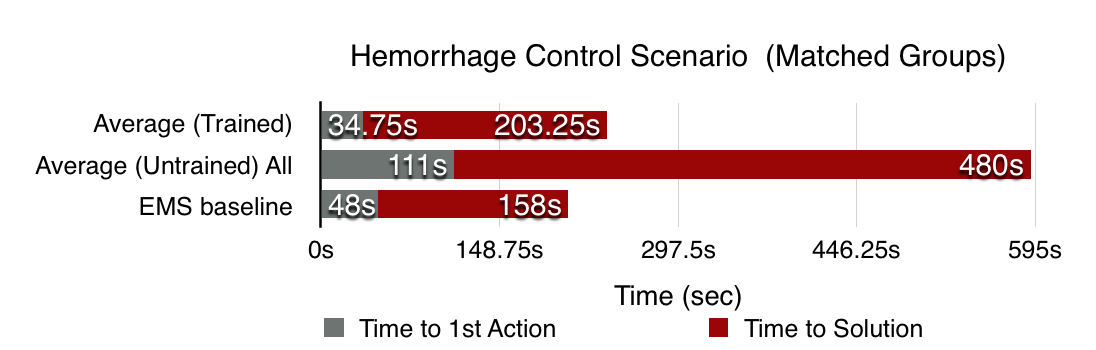

Through a series of exercises held during First Care provider training sessions, we have found that average people with as little as a half day of training are almost as effective as trained responders in recognizing critical issues like bleeding and intervening.

Trained = Civilians who have completed First Care Training

Untrained = Civilians before any training

EMS = Trained EMTs, Paramedics and RNs

Becoming a truly resilient community

In summary; to be a truly resilient community, we much teach people how to rely on themselves in the critical first 5-7 minutes it takes for even the most robust response systems to reach the victims of traumatic injury.

First responders have to start looking at their residents as force multipliers instead of hapless bystanders that need to be moved out of the way during an emergency.

As emergency responders, we have to dispel the illusion that we will always be there in time to make a difference. We have to acknowledge and prepare citizens for the reality that with a modest amount of training, those on site during an emergency can provide meaningful and effective first care before the professionals arrive.

About the author

Chief Wylie is a 29-year fire service veteran who retired as fire chief of the Cottleville FPD in St. Charles County, Mo. Rob has served as a tactical medic and TEMS team leader with the St. Charles Regional SWAT team for the past 19 years. He is a certified instructor and teaches at the state, local and national level on leadership, counter terrorism and TEMS operations. He graduated from Lindenwood University, the University of Maryland Staff and Command School and the National Fire Academy’s EFO Program. Chief Wylie is a member of the Fire Chief/FireRescue1 Editorial Advisory Board. You can reach him at Rob.Wylie@FireRescue1.com.