By Pam Farber, RN, EMT-P; Rob Lawrence

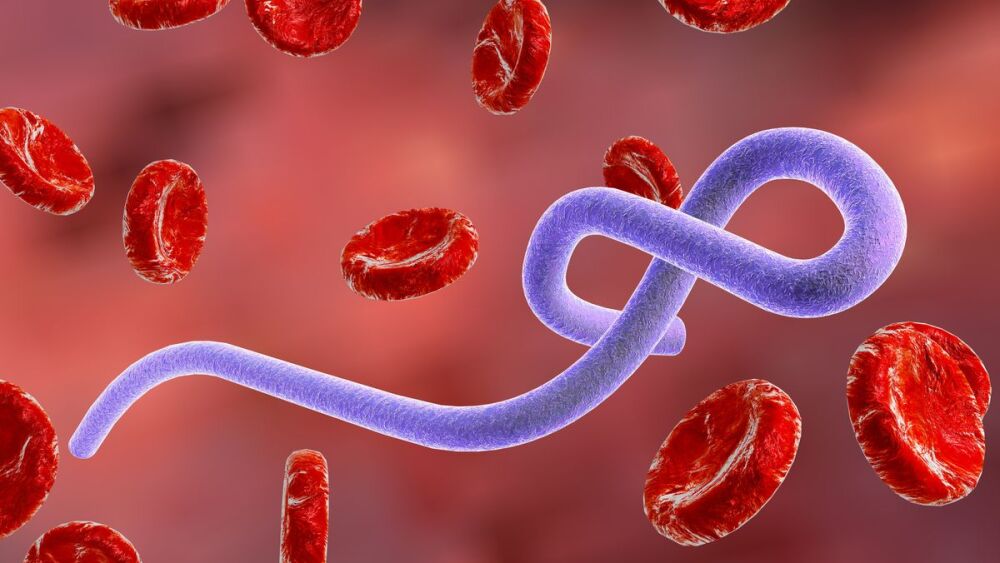

On September 20, 2022, Uganda announced that it had an outbreak of Ebola Virus with the Sudan strain, which has now spread amongst five of its administrative districts. The case and death count, as of October 12, 2022, was 74 total cases (54 confirmed) and 39 deaths (19 confirmed). Ten of the cases reported were healthcare workers; four have recovered, four have died.

The affected areas are close to the country’s capital, Kampala, a busy and mobile area, with easily traveled roads and close access to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), increasing the possibility of someone being infected. Fortunately, Uganda has dealt well with Ebola outbreaks in the past and has quickly put measures in place to prevent outward spread and to provide containment of those infected.

Alert and advisory

As a result of this outbreak, the U.S. has issued a Health Advisory Network (HAN) Travel Alert Level 2 and HAN Health Advisory for healthcare workers to be aware of the Ebola outbreak in Uganda, monitor for symptoms consistent with Ebola, and utilize best practices if there are any signs that someone might be experiencing an illness consistent with it.

Canada has also encouraged those traveling to Uganda to practice enhanced precautions and monitor for Ebola illness, especially associated with travel from the Uganda area.

Vaccine

Ebola Sudan Virus is a much rarer virus compared to the Zaire strain, although there have been seven previous outbreaks of it since 1977. There are no treatments for it, other than supportive care with fluid and electrolytes, respiratory and other care, as needed. The vaccine that was successful against the Zaire strain does not appear, in animal studies, to have any effect against the Sudan strain. There are currently two vaccines in early human trials which may help prevent or decrease the impact of the Sudan strain.

Travel precautions

Both the U.S. and Canada are considered low risk for spread of Ebola at this time. The US doesn’t receive direct flights from Uganda, although visitors or Ugandan citizens could be exposed and then travel elsewhere to board a flight or ship. As an extra precaution, any passengers flying into the U.S., who have been in Uganda in the 21 days before their arrival in the U.S. will be routed to one of five designated U.S. airports for enhanced Ebola screening – JFK airport in New York; Liberty International in New Jersey; Dulles International in Washington, D.C.; O’Hare International Airport in Chicago, or Hartsfield-Jackson International in Atlanta.

Abundance of caution

The government will continue to monitor the current Ebola outbreak, work with other international, federal, state and local partners, and adapt public health policy and guidance accordingly. A regional treatment network for Ebola and other special pathogens has been set up to assess, mitigate and begin management for patients who may have Ebola or other public health high risk disease. This system consists of NETEC’s Special Pathogens Partners, Regional Treatment Centers and HHS Regions.

Actions for agencies

- Identify. Identify at least one person in your agency to monitor the Ebola situation and watch for any changes to the current recommendations. FirstWatch operates in both the U.S. and Canada, and will constantly advise on changes in both countries via its Health Intelligence page.

-

Develop and review. This is a good time to review and update Ebola policies and procedures in place at your agency. The medical director and/or a well-educated and experienced infection control practitioner (designated infection control officer and/or your occupational health service), should review the policy for medical correctness and practicality. Consult with local public health authorities for assistance when needed.

These policies and protocols should include (nation-specific) components of the:

Also, take time to review the current plan for the Regional Treatment Network for Ebola & Other Special Pathogens. and note that three hospitals have been designated as National Ebola Training & Educational Centers (NETEC). They include Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Ga; University of Nebraska Medical Center/Nebraska Medicine in Omaha, NE; and NYC + Hospitals/Bellevue in New York City. All three have successfully treated patients with Ebola. Follow the link for their site containing further references and resources.

- Liaise and train. If you haven’t already done so, develop relationships with your local public health physician, administrator, and those that have responsibility for night and weekend calls (typically RNs or APs). If your local health department participates as a biological and/or chemical lab, meet the director and staff there, as well. These relationships may become useful with Ebola. Also, take the opportunity to conduct tabletop exercises with them to rehearse plans and identify, in a training environment, issues you may encounter with a “live”’ Ebola patient. Also, include your hospitals’ infection prevention and control and/or occupational or employee health practitioners in your discussions and tabletop exercises.

- Assess and prepare. Assess your current stockpile of “special hazards” PPE; tape used to secure PPE; disposable, single-use equipment; EPA-approved Ebola disinfectants; other items needed for deconning personnel, any non-disposable equipment, as well as the vehicle; and any other items that may be required if Ebola expands outside of Africa.

The acceptance of sub-standard equipment during the COVID Pandemic because there wasn’t enough of the “real stuff” available, will not suffice with Ebola. There must be authentic medical (not industrial grade) N95 masks, and not counterfeit ones (the counterfeits can really fool you), KN95s (China), KF94s (Korea) or any other substitute. The filters for PAPRs must be the correct ones for high-risk pathogens and NIOSH approved. The gowns/jumpsuits and aprons need to be resilient enough to not rip during EMS operations. Department heads may have to reach out to government officials to point out this essential need and remind them that special pathogen stockpiles have been depleted to meet COVID needs. Certified & approved replacements may still be hard to procure.

Listen for more:

EMS strategies for Ebola with Dr. Alex Isakov

Identify, isolate, and inform: The current situation on COVID, Ebola and Monkeypox

Additional resources for Ebola management

- CDC Healthcare Worker Guidance for PPE with Ebola Risk: Unstable/"wet” patient

- CDC Healthcare Worker Guidance for PPE with Ebola Risk: Stable/"dry” patient

- CDC PPE FAQs (10/20/20)

- NAEMT Article on lessons learned from the travel-related Dallas Ebola patient

- EMS1 article about How Grady prepared for Ebola patient transports

- NIH article on EMS public health implications

About the author

Pam Farber, RN, EMT-P

Pam Farber has worked in medicine for 40 years, first as an RN, then adding firefighter/paramedic, with more than two and a half decades as the paramedic instructor, infection control officer, and IAED EMD instructor for City of Miami Fire-Rescue. She also provided expertise in bioterrorism and MCIs, hazmat/toxicology, first responder occupational health, medicolegal issues, CQI and medical chart review, and policy and protocol development. She served as past chair and current member of the IAED CBRN Committee and volunteer faculty for the University of Miami.

Pam has worked with FirstWatch for more than 10 years, first as a clinical advisor, and then as public health advisor. In her role, she provides information and related articles on infectious disease outbreaks and other public health issues, first responder health and safety, and pandemic awareness and planning, often adding how EMS and other first responders can put this information to use.