Highlights:

Introduction

The review

What this means for you

Introduction

Rescue 16 responds to a motor-vehicle collision at an intersection. Engine 16 arrives first and reports a single patient with heavy damage intrusion to the patient’s side of the vehicle.

Once the ambulance arrives, the fire lieutenant reports popping the door with hand tools and one of the firefighters placed a cervical collar on the patient’s neck. The medic finds a female, age 28 conscious and alert, sitting behind the steering wheel. He estimates about a foot of damage intrusion into the passenger compartment. The patient is frightened with multiple small scratches on her left arm, shoulder and face, but otherwise without significant complaints. The patient is able to move all extremities well and her vital signs are all within normal limits. The medic’s head-to-toe physical exam is unremarkable for significant trauma.

The rescue team gently moves the patient to a backboard and completes spinal motion stabilization. The patient asks for transport to the community hospital where her mother works, which is about 10 minutes from the scene. The level one trauma center is about 30 minutes away in the opposite direction. Rescue 16 begins transport to the community hospital.

After transferring patient care to the emergency department (ED) nurse, the medic begins completing the patient care report. Within a few minutes, the ED physician approaches and asks about vehicle damage. After hearing about the intrusion, the physician asks why the medic did not transport the patient to the trauma center. The medic attempts to explain that the patient had no significant injuries and likely did not require trauma services. The ED physician explains that the patient met the mechanism of injury criteria for transport to a trauma center adding that there is no way for the medic to rule out significant trauma when excessive impact forces are involved. The physician states the medics should have transported her to the trauma center based on mechanism of injury alone.

Review

Researchers in Connecticut sought to determine the accuracy of using mechanism of injury as the sole predictor of a patient’s need for trauma center resources (Isenberg, Cone, & Vaca, 2011). Analysts searched the ED medical records at two hospitals for patients who arrived by ambulance after being involved in a motor-vehicle collision (MVC). One hospital was a level-one trauma center and the other was a freestanding satellite ED. Researchers included patients transported to the satellite ED in order to capture those who actually met the triage criteria but did not go to the trauma center for whatever reason.

After identifying the patients involved in the MVC, the researchers attempted to match each ED chart to the patient care record (PCR) completed by the ambulance crew. The team then used the ambulance PCR to gather information about the mechanism of injury.

During the medical records search, the researchers identified patients who met certain mechanism of injury criteria but did not have any anatomical injuries or physiological abnormalities that required trauma team evaluation. For mechanism of injury, the researchers chose the vehicle intrusion criteria established by a national expert panel on field triage assembled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Sasser et al., 2009). These criteria recommend a trauma center destination if the patient occupied a vehicle that suffered damage intrusion into the passenger compartment of more than 12 inches (31 centimeters) at the occupant’s site or more than 18 inches (47 centimeters) at any other site. The CDC clarifies that in the absence of physiologic abnormality (vital signs) or anatomical injury, the receiving facility could be any hospital that meets one of the four levels of trauma center designation established by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (American College of Surgeons, 2006.) and not necessarily the highest-level trauma center.

After identifying the patients occupying vehicles that met the intrusion criteria, the researchers evaluated the medical records for two outcome measures. First, the researchers determined if the ED physicians admitted the patient to the trauma service department within the hospital. They excluded patients admitted to other areas of the hospital, such as a medical floor for a seizure that may have caused the original collision or an orthopedic ward for a simple fracture occurring during the collision. For the second outcome measurement, the researchers also reviewed the medical records to determine if any patient actually needed trauma services despite their admission location. The researchers predefined a patient’s need for trauma service resources based on the presence of one of the following criteria:

- Death as an inpatient

- Admission into an intensive care unit

- Patients receiving a surgical intervention of any kind after admission to the hospital

- Spinal injury of any degree

- Intracerebral hemorrhage

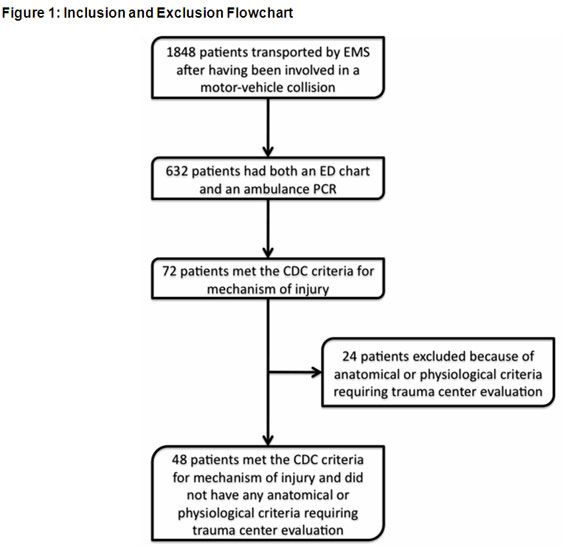

Figure 1 diagrams the method used to obtain the study population. During the 18-month study period, medics transported 1350 adult patients and 498 children following involvement in a MVC. Of those, the research team could only find ED charts and ambulance PCRs for 632 patients. Of those, 72 patients met the CDC criteria for vehicle intrusion. The researchers excluded 24 of those because they also met the anatomical or physiological criteria for transport. This left 48 patients transported to the trauma center based solely on the vehicle intrusion guidelines established by the CDC.

The occupants of vehicles suffering intrusion were younger, more likely to be restrained, and involved in a single-vehicle crash (p-values less than 0.05 indicate the difference between the two groups meets statistical significance and is not likely due to chance alone). Table 1 describes the demographic differences between the patients.

Table 1: | No Intrusion | Intrusion | p-value |

Age—mean ± standard deviation | 33.9 ± 19.8 years | 29 ± 4.7 years | < 0.01 |

Gender - female | 323 (57%) | 23 (48%) | 0.22 |

Restrained in vehicle | 438 (78.2%) | 30 (62.5%) | 0.02 |

Highway crash | 372 (66.4%) | 38 (79.2%) | 0.07 |

Single-vehicle crash | 148 (26.4%) | 24 (50%) | 0.001 |

This study is essentially an evaluation of the accuracy of a diagnostic test – in other words, can the test (presence of absence of significant intrusion) accurately predict who will have the condition (need for trauma center resources or admission). Table 2 displays the results of the initial analysis.

The first data row shows the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) of using intrusion alone (as a diagnostic test) to determine whether physicians will admit patients to the trauma services department. Sensitivity represents the chances of someone testing positive that really has the condition (Altman & Bland, 1994). For this study, test sensitivity is 39%, meaning that about 4 out of ten patients who tested positive (significant intrusion) actually had the condition (admitted to trauma services. Remember that the inclusion criteria also required these patients to be free from anatomical injury and physiological abnormality. There was a reason that the ED physicians admitted these patients to trauma services, but it was not because of damage intrusion.

Table 2: | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value |

Intrusion for trauma service admission | 91.9% | 92.8% | 25.5% |

Intrusion for utilizing trauma service resources | 58.3% | 91.9% | 12.7% |

To illustrate the concept of sensitivity further, suppose a pharmaceutical company markets an over-the-counter test with 39% sensitivity for discovering pregnancy. If 100 pregnant women take the test, 39 will correctly test positive but 61 women who really are pregnant will have test results that indicate they are not. It is likely that consumers would consider the product worthless.

Specificity refers to the accuracy of a negative test result correctly identifying someone who does not have the condition. In this study, 93% of the occupants with a negative test (no significant damage intrusion) did not have the condition (admitted to trauma services). This is actually a very good result - if there were no physiological abnormality, no anatomical injury, and no damage intrusion, physicians rarely admitted the patient to the trauma services department. Using the home pregnancy test example, 93% specificity means that if the test results suggest that a woman was not pregnant (negative result), she could be reasonably sure that she really was not pregnant.

Finally, the PPV is the chance of having the condition among the group who tested positive. For this study, the PPV of damage intrusion was 25.5%, meaning that of everyone who tested positive (significant intrusion), only about one-fourth had the condition (trauma services admission). In the pregnancy test example, a PPV of 25% means that one-fourth of all the women who test positive will actually be pregnant – not a very reliable predictor.

The second data row shows the sensitivity, specificity, and PPV of using intrusion as the sole criterion for determining if admitted patients really needed trauma service resources. Remember that the first outcome measure included patients admitted to trauma services – not the hospital in general. Physicians admitted some patients to medical-surgical or orthopedic floors and the research team excluded those patients from analysis using the first outcome measure. This second measure allows the team to evaluate those patients to determine if the physicians SHOULD have admitted them to trauma services.

Interestingly, that outcome measure actually increased sensitivity. This suggests that about 58% of the patients who tested positive (significant intrusion) had this new condition (utilized trauma service resources) even though they were not all admitted to the trauma services department. Although sensitivity improves, damage intrusion still misses about 42% of patients without anatomical of physiological abnormality who actually utilizes trauma service resources.

Specificity remains very high (91.9%) with this outcome measure suggesting that vehicle occupants with a negative test (no significant damage intrusion) did not likely need any trauma service resources.

However, the PPV in the second row is miserably low. This means that among the group of patients who tested positive (significant damage intrusion), less than 13% actually had the condition (needed trauma service resources).

The authors conclude that damage intrusion into the passage compartment in the absence of anatomical injury or physiological abnormality is a poor predictor of admission to trauma services or the need for trauma service resources.

What this means for you

Other researchers have examined the accuracy of using passenger compartment intrusion as the sole predictor of severe injury following MVC (Henry, 2006; Long, Bach, & Hynes, 1986; Palanca, Taylor, Bailey, & Cameron, 2003; Simmons, Hedges, Irwin, Maassberg, & Kirkwood, 1995). Collectively, these studies do not provide strong support for using this criterion alone as a reliable triage tool for selecting patients that require trauma center destinations. The CDC acknowledges the weak support but did not believe it appropriate to remove the criterion from the trauma triage schematic for prehospital personnel.

After the initial analysis, the authors substituted entrapment for vehicle intrusion as an inclusive criterion and performed a secondary analysis. Researchers frequently perform these post hoc analyses when they identify a trend that they did not expect during the initial study design. One cannot draw a persuasive conclusion from a post hoc analysis, but it does provide direction for further exploration.

During the primary analysis, researchers noticed that medics often did not record the degree of vehicle intrusion for patients trapped in their vehicle following the collision - they merely recorded patient entrapment. It is reasonable to assume that significant damage intrusion may have trapped some of these patients. The authors defined a trapped patient as one that rescuers extricated with the use of power tools. That definition automatically excluded patients where the fire department merely popped a jammed door.

Table 3 shows the sensitivity, specificity, and PPV of using entrapment instead of damage intrusion as the predictor of trauma service admission and the need for trauma service resources. Entrapment only slightly improved sensitivity for trauma service admission but was much more sensitive for utilization of trauma service resources. Entrapment improved specificity for both outcome measures meaning that if there was no entrapment, there was no need for trauma service admission or trauma service resources. Using entrapment instead of intrusion tripled the PPV for trauma service admission (25.5% vs. 80.0%) and more than quadrupled the PPV for utilization of trauma service resources (12.7% vs. 55.0%).

Table 3: | Sensitivity | Sensitivity | Sensitivity |

Entrapment for trauma service admission | 44.4% | 99.3% | 80.0% |

Entrapment for utilizing trauma center resources | 91.7% | 96.8% | 55.0% |

The authors note that using entrapment instead of intrusion as a triage criterion would have resulted in 16 fewer patient transports to the trauma center. One of those patients suffered a hip dislocation that the ED physician non-surgically reduced but admitted to trauma services for overnight observation. None of the other 15 patients required trauma services.

Since the present study is a retrospective analysis, it cannot establish cause and effect relationships. Retrospective studies do not allow researchers to control variables that can influence the outcome. This study design simply provides insight for future studies.

One limitation of the present study lies in the outcome definitions used for selecting patients. Although admission to the trauma services unit seems straightforward and unambiguous (patients were admitted or not), there is no uniform definition of what constitutes the need for trauma service resources. The authors arbitrarily chose their criteria. Other researchers using different criteria may find different results (Evans, Nance, Arbogast, Elliott, & Winston, 2009).

Another limitation is the small number of patients who met the researcher’s criteria for inclusion in the study. During the 18-month study period, emergency medical service (EMS) personnel transported 1848 trauma patients but ultimately only 48 met the criteria for damage intrusion without significant injury or physiological derangement. As the authors point out, this could reflect the fact that patients in vehicles with this degree of damage may also have anatomical or physiological evidence of serious injury.

However, it is also reasonable to assume that missing and illegible prehospital charts may have ultimately reduced the number of patients who met the inclusion criteria. The researchers found both a hospital medical record and a prehospital PCR for about one-third of the trauma patients. The authors report this as a chronic problem in their area made worse by the fact that the EMS system uses paper records. The authors are hopeful that EMS system conversion to electronic patient records will correct the problem.

Finally, variability between medics attempting to estimate damage intrusion may have influenced the results. Field estimates are purely subjective as there is no practical and objective way to measure this on the scene. As a result, several medics could see the same degree of intrusion but have different interpretations of its significance thereby making some eligible for trauma centers while excluding others. Despite this reality, one study actually found no significant difference between intrusion estimates by prehospital personnel and actual intrusion measurements obtained by trained crash investigators (Lerner et al., 2009).

There is very little evidence supporting the use of damage intrusion as the sole criterion for determining the need for trauma services resources, a fact acknowledged by an expert panel on field triage. Since the birth of modern EMS, improvements in vehicle design and the addition of safety features has altered crash worthiness of commercial automobiles in the United States. Damage intrusion may no longer play a prominent role in field triage thereby requiring a reexamination of field triage criteria. Simple changes to current standards may improve the triage ability of the street medic thereby allowing appropriate destinations of those patients who will benefit from trauma center evaluations while not over burdening those specialized facilities with patients who do not need to be there.

References

Altman, D. G. & Bland, J. M. (1994). Diagnostic tests. 1: Sensitivity and specificity. British Medical Journal, 308(6943), 1552.

American College of Surgeons. (2006). Resources for the optimal care of the injured patient: 2006. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons.

Evans, S. L., Nance, M. L., Arbogast, K. B., Elliott, M. R., & Winston, F. K. (2009). Passenger compartment intrusion as a predictor of significant injury for children in motor vehicle crashes. Journal of Trauma, 66(2), 504–507. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318166d295

Henry, M. C. (2006). Trauma triage: New York experience. Prehospital Emergency Care, 10(3), 295-302. doi:10.1080/10903120600721669

Isenberg, D., Cone, D. C., & Vaca, F. E. (2011). Motor vehicle intrusion alone does not predict trauma center admission or use of trauma center resources. Prehospital Emergency Care, 15(2), 203–207. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2010.541977

Lerner, E. B., Cushman, J, Blatt, A, Lawrence, R., Shah, M., Swor, R., Brasel, K., Jurkovich, G. (2009). A comparison of EMS provider assessment of mechanism of injury criteria in a motor vehicle crash with expert measurement of motor vehicle damage [abstract]. Academic Emergency Medicine, 16(suppl 1), s198. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00391.x

Long, W. B., MD, Bach, B. L., & Hynes, G. D. (1986). Accuracy and relationship of mechanisms of injury, trauma score, and injury severity score in identifying major trauma. The American Journal of Surgery, 151(5), 581-584. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(86)90553-2

Palanca, S., Taylor, D. M., Bailey, M., & Cameron, P. A. (2003). Mechanisms of motor vehicle accidents that predict major injury. Emergency Medicine, 15(5-6), 423-428. 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2003.00496.x

Sasser, S. M., Hunt, R. C., Sullivent, E. E., Wald, M. M., Mitchko, J., Jurkovich, G. J., Henry, M. C., Salomone, J. P., Wang, S. C., Galli, R. L., Cooper, A., Brown, L. H., Sattin, R. W. and the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2009). Guidelines for field triage of injured patients. Recommendations of the national expert panel on field triage. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review: Recommendations and Reports, 58(RR-1), 1–35.

Simmons, E., Hedges, J. R., Irwin, L., Maassberg, W., & Kirkwood, H. A. (1995). Paramedic injury severity perception can aid trauma triage. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 26(4), 461– 468. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70115-X